| Index | Next |

DELTA AIRLINES INFLIGHT MAGAZINE

MODE: Sports

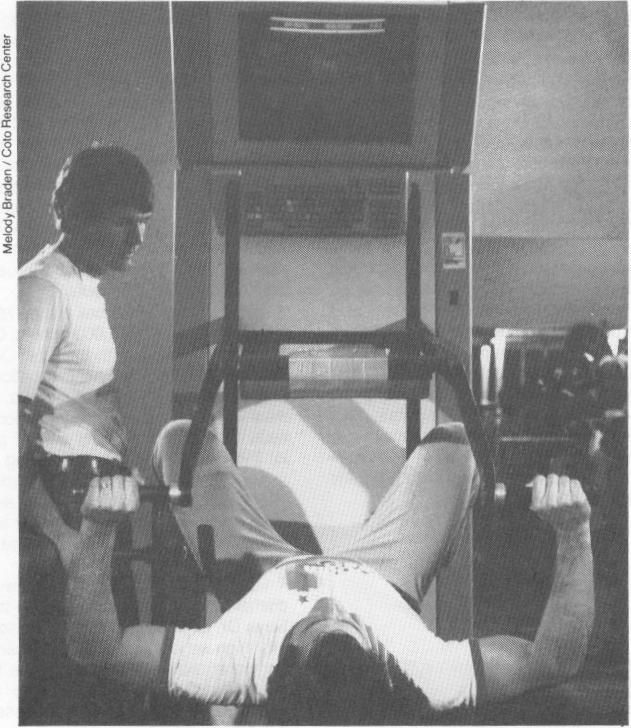

At Coto Research Center, $3 million worth of computer technology helps athletes improve abilities.

Power hitters slugging 80 homers a season ... running backs rushing for 3,000 yards a year ... milers streaking across the finish line in 3:30 ... pole vaulters clearing the bar at 20 feet.

These unparalleled sports achievements are within the grasp of athletes who seek greatness and goals through the new science of biomechanics: the computer analysis of athletic motion.

In its infancy, biomechanics is already doing more to raise the limits of human performance than all the steroids ever injected. And by the year 2000, computerized exercise equipment and ultra-sophisticated measuring devices will be as much a part of the training room, clubhouse and

health spa as Nautilus equipment is now.

"Anything you can do, you can do better through biomechanics - even if you're a superstar," declares Gideon Ariel, the Vince Lombardi of biomechanics. "Some superstars could do 50 percent better."

That's because the John McEnroes, Walter Paytons and Sugar Ray Leonards of today simply haven't reached their physical limits yet. But tomorrow's stars will approach the threshold of their own athletic perfection through biomechanics, says Ariel.

He heads the Coto Research Center in Coto de Caza, California, a sports clinic which relies on $3 million worth of computer technology to enhance athletes'

physical rehabilitation and improve their performance.

Experts like Ariel film an athlete in action using highspeed movies which are converted to frames of stick figures for computer analysis. Detailed calculations then are made of body movement, timing and forces that create or result from movement.

The information gained can do more to improve performance than weeks of practice. For example, Ariel's computer showed that U.S. Olympic discus thrower Mac Wilkins was not striding right, causing his front leg to absorb energy that could otherwise be utilized in his throw. Wilkins changed his stride and shattered the world record at the time by nearly six feet.

When Jimmy Connors' serve was computer analyzed, Ariel discovered that the tennis star's feet were leaving the ground at a crucial moment, reducing the velocity of his serve by 20 miles per hour. Connors made the necessary adjustments and sped up his serve.

The feats of today's stars could seem commonplace by the year 2000, says Bob Ward, conditioning coach for the Dallas Cowboys. "If we do a biomechanic analysis on (running back) Tony Dorsett and find he's playing at only 60 percent of his physical capabilities, we'd help him make a few adjustments. Then there'd be no reason why he couldn't rush for 3,000 yards a season.

"Computers will help improve the quality of players and, as a result, there isn't a single record that couldn't be broken."

Although biomechanics will identify weaknesses and assign proper training instructions and adjustments, it cannot measure one very important factor: the athlete's state of mind. "Biomechanics can't consider his psychological makeup, desire to achieve or other outside factors which could affect performance," admits Ariel.

Nevertheless, Ariel, who is chairman of the Biomechanical Committee of the U.S. Olympic Committee, believes the new science will help the athlete "to the point where the body is performing at its peak; when the anatomical structure can't perform any better."

Biomechanics will assist the athlete in another way - improved sports equipment. "Bugging" golf clubs, tennis racquets and ski poles with electronic sensors is already spurring new designs and manu

SKY July 1982

| Index | Next |