| Previous | Index | Next |

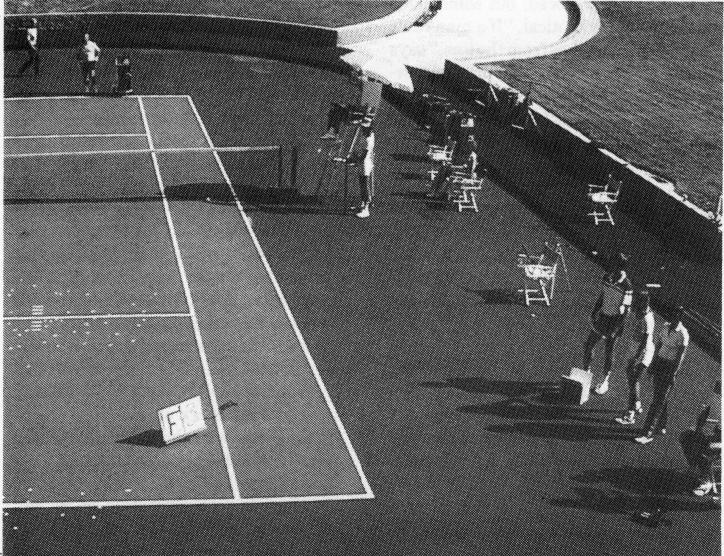

dressed in tennis clothes mill around a court amid a profusion of electrical and camera equipment. One man is smashing serves over the net while a sonic speed gun registers velocities of up to 108 miles an hour. Just before each serve, two high-speed movie cameras at the sides of the court begin to whir. Immediately afterward, four assistants race out to the service line with colorcoded sticks to mark the spots where the two linesmen, the chair umpire, and the receiver say they saw the ball hit.

On this serve, the sticks are divided evenly-two on each side of the line. "You see?" says an exasperated Vic Braden, turning from one of the cameras. "If this was a professional match, somebody would say he was robbed!"

Braden, 53, a pudgy, cherubic-faced tennis pro, is best known for his television appearances as a commentator at major matches and a humorous purveyor of tennis tips for hackers. But he is also a leading tennis theoretician (DISCOVER, February 1981) who holds a master's degree in educational psychology. He was chosen by the Umpires Committee of the United States Tennis Association to explore the controversial subject of line calls, to find out what factors make a line call accurate or inaccurate. The umpires may be sorry they

asked. As Braden says, "We never really knew how bad people are" at seeing where a ball hits.

The tenure of officials in major tennis tournaments is more precarious than in almost any other sport. The umpire can dismiss a linesman in mid-match, and be ousted himself-if he loses control of the players-by the tournament referee. As a result, tennis players, more than most other athletes, are able to intimidate officials. Says Braden, "Some players I know don't dispute a call to dispute the call, but to pre-set the official's brain for the next call." Even the crowd can have an influence. "The officials are caught between calling the score right and survival. It's a war down there."

Braden has now stepped into the line of fire with evidence that often neither players nor officials really see where the ball lands-whether at a service line, a baseline, or a sideline. That conclusion is drawn partly from studies done with the Eye Mark Recorder, a helmet-like device that bounces a tiny light otl' the wearer's pupils to reveal (in the form of a dancing dot on movie film) where the eyes were focused. In tests, the Eye Mark Recorder showed that the linesman's gaze was not always directed at the spot where the ball landed.

Moreover, a fast serve is actually in contact with the ground for only about three thousandths of a second. That is less time than a single flicker of a 60-cycle-per-second fluorescent light bulb, and Braden maintains that the contact occurs too fast for the eye to register it. "McEnroe always says, 'Right here! It was right here!' "says Braden. "But it's a joke. He can't know that."

The protests are probably made in good faith; the evidence seems to show that a player sees the ball before it lands and then after it bounces, and that his brain (by using triangulation based on the ball's incoming and outgoing trajectories) tricks him into thinking he has seen the landing spot. But the brain itself can be tricked. Studies by Gideon Ariel, an Israeli-born former Olympic discus thrower and director of the Coto Research Center, a $5 million sports laboratory adjacent to the Tennis College, show that a tennis ball does not bounce cleanly but can slide as much as two or three inches along the court. Moreover, it always bounces up at a steeper angle (the increase ranges up to 15 degrees) than the angle at which it approached. The change in angle, Ariel says, could throw off the brain's triangulation process.

A player's perception may also be distorted by movement of his head, which creates mini G-forces that can deform the eyeball for an instant, putting the images on the retina out of focus. "If you have twenty-twenty vision," Braden maintains, "when your foot hits the ground, for a moment you are legally blind." Players suffer from this, of course, but linesmen are not immune: in less important tournaments, with fewer officials on hand, a linesman must sometimes watch the center service line for the serve, then run to a sideline for the rest of the point.

In major tournaments, with linesmen at every line, there is no need for running. And it was from fixed positions that the linesmen scored well in Braden's tests. In 204 calls recorded on film, their estimates of where the ball hit were off by an average of less than two inches, and they had only one outright miscall-an error rate of about one-half of one per cent.

Umpires, perched in high chairs at one end of the net, fared less well. They had two miscalls in 73 attempts, a 3 per cent error rate, and an average error of almost three inches per call. Worst of all were the players: they misestimated the

1

DISCOVER December 1982

| Previous | Index | Next |