| Previous | Index |

![]()

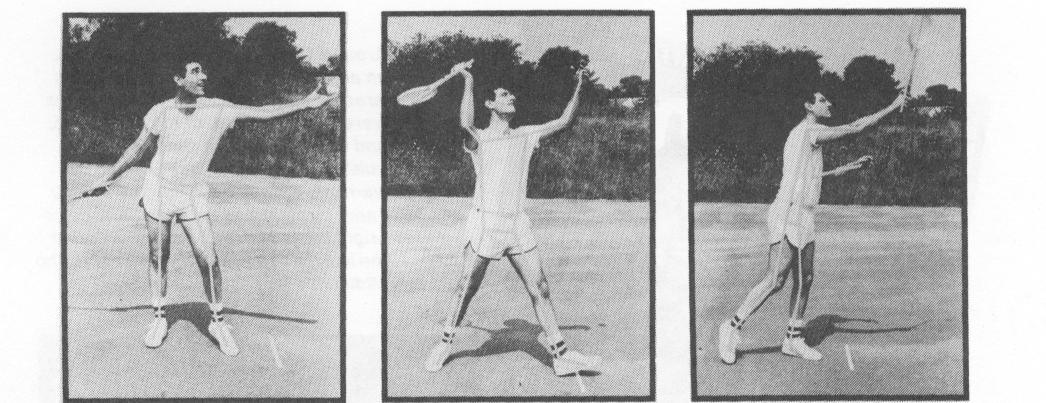

The computer breaks down a beginner's serve into a sequence of stick figures. By comparing a student's stroke with that of a "model" stroke, a teaching pro can make corrections. The computer's stick figures are printed from a high speed camera, and then biomechanical analysis by the computer reveals how the serve can be changed for maximum effectiveness.

Ariel has spent the last few years showing athletes how to maximize their efforts, or, in the case of tennis players, how to optimize their talent. His firm, Computerized Biomechanical Analysis, is situated in Amherst, Massachusetts with a staff of 12, six full-time. It is only one of the corporate arms that Ariel has set up to handle a mounting list of clients that has included the Dallas Cowboys, Kansas City Royals, AMF, Dow Chemical, and Kimberly Clark.

It is also a far cry from Ariel's humble beginnings at a boarding school outside of Tel Aviv and his early academic pursuits at the University of Massachusetts. Ariel laughs when he recalls the long days, and even longer nights spent in pursuit of his master's degree after he had completed three years at the University of Wyoming. But there is little doubt that as sports entered the computer age, Ariel was quick to sense that technology was not being tapped.

Ariel's secret is programming tons of raw information into a computer through a device known as a "digitizer," a screen lined on two sides by 20,000 tiny directional microphones. The coordinates of any point on the screen touched with a sonic pen are registered and fed into the computer.

Some of Ariel's demonstrations, using stick figures, frequently leave audiences gasping in awe. Advanced courses in calculus and cybernetics have hardly held any priorities in sports alongside phys ed. Some skeptics believe that Ariel is not really saying anything that coaches do not already know.

But Ariel has an impressive routine, filled with familiar comparisons. In discussing the relative importance or nonimportance of stringing, Ariel says, "When you play a violin, how do you produce different sounds? By pulling different points?" Ariel equates the role of the digitizer in tracing the location of the ball to the same principle of searching for a room in a hotel.

What has strengthened Ariel's credibility is his results with such prominent athletes as Mac Wilkins, the Olympic discus champion, and Terry Albritten, a world-class shotputter. Wilkins set a world record in the discus after Ariel showed him that there was a disproportionate share of speed in one section of his spin. Ariel's high-speed films of U.S. Olympic kayakers and volleyball players has also prompted significant revisions in their training procedures.

"Tennis players think they can feel the ball on the racket," he says. Actually, Ariel says, a tennis ball is on the racket about four milliseconds, or four one-thousandths of a second. Normal human reaction time is 60 milliseconds. Conclusion: The ball is gone before anyone feels it.

Some of Ariel's other findings may also have tennis teachers wondering what to tell students at their lesson. They include the following:

O There is little difference in the efficiency of nylon and gut. Nylon can accomplish as much if you string it properly.

LI There is no such thing as a "trampoline" effect on a tennis racket. The ball hits and leaves too quickly.

• The "spaghetti" racket significantly increases the spin on a ball by "grabbing" the ball and altering its normal trajectory. Thus, playing with the spaghetti racket, now banned from Grand Prix tournaments, could be an advantage to some players.

• The key to early racket preparation is not so much moving the racket but turning the shoulder first before getting the racket back. In order to create energy, it is necessary to turn the hip and trunk.

• The speed guns that measure the so-called 100-mph serves of top players are "very inaccurate." In one experiment, Ariel said he measured a serve of Vijay Amritraj, supposedly clocked at 100 mph with a speed gun. On the computer, the serve was clocked at 70 miles per hour.

Van der Meer and Ariel do not believe that computers can solve every problem in tennis, particularly at the beginner level. But the possibility of providing a standard, systematic form of teaching may lead to more accuracy in visual observation.

"The human element cannot be measured," Ariel conceded. "You cannot account for a tendency by someone to be more inefficient and yet produce a result, such as hitting a volley near the net. You cannot say biomechanics are going to solve everything in tennis. But you want certain things, and if it can allow the teaching pro not to guess at something because he has all the data, look how far we can go to upgrade teaching methods, prevent injuries, and make it a better game." 0

WORLD TENNIS MARCH 1979

![]()

| Previous | Index |