| Previous | Index |

Ariel, a burly Israeli who competed in the 1960 and 1964 Olympics as a discus thrower and shot-putter, was still a graduate student at Dartmouth in 1971

when he founded his own company, Computerized Biomechanical Analysis, Inc., which made use of the college's newly instituted time-sharing computer system. Then Ariel moved to the University of Massachusetts, where he used that school's computer to refine his system of hiomechanical analysis. In 1975, after reading a SPORTS ILLUSTRATED profile of Braden, Ariel called and arranged a meeting at Coto de Caza. Braden recalls, "I was already involved in high-speed cinematography, and I was discovering that many things being said about sports techniques by a lot of big names were simply not true-and terribly misleading. Then I met Gideon, who was already one step ahead of me by computerizing what was actually happening, working oft' high-speed film. So it was a perfect marriage. We started talking about our dreams for a research center at about four in the afternoon, and when I thought it was time for din

ner, it was about three in the morning. We were ten or fifteen years ahead, thinking about what was going to happen to sports, and the kind of research we could be doing." Recalls Ariel, "I told Vic I couldn't see a better place in the world to have a research center like this. It took us five more years, but we had this dream and we didn't let it go until it happened. Now we must make it work."

I f enthusiasm and ingenuity are enough to make it work, then the Coto Research Center will triumph. The two-story building houses comprehensive computer-equipment hubs, laboratories, exercise and workout areas, shower facilities, offices, and conference and projection rooms. About the only thing that it does not

have is room for improvement.

One of the unique aspects of the center is that an athlete can be filmed inside the facility, close to all the monitoring equipment, while performing in a realistic situation. A net comes down from the roof, allowing the athlete actually to hit a golf ball, pitch a baseball, throw a discus, or even, presumably, toss a caber. There is a trap door in the roof to allow filming from above, which provides an excellent perspective for studying the efficiency of body movement. Placing an athlete in laboratory conditions turns out to be the ideal way to assess his performance. Explains Ariel, "He doesn't have to concern himself' with distance or accuracy. He just focuses on technique."

But llraderr and Ariel also plan to monitor top athletes in competition,

taking their high-speed cameras to track meets, tennis tournaments, basketball games, and other athletic events to film their students under stress. Braden, who holds a graduate degree in psychology, is interested in knowing what happens "when the adrenaline is flowing differently. When we take an athlete into the lab, does he perform and execute the same way?"

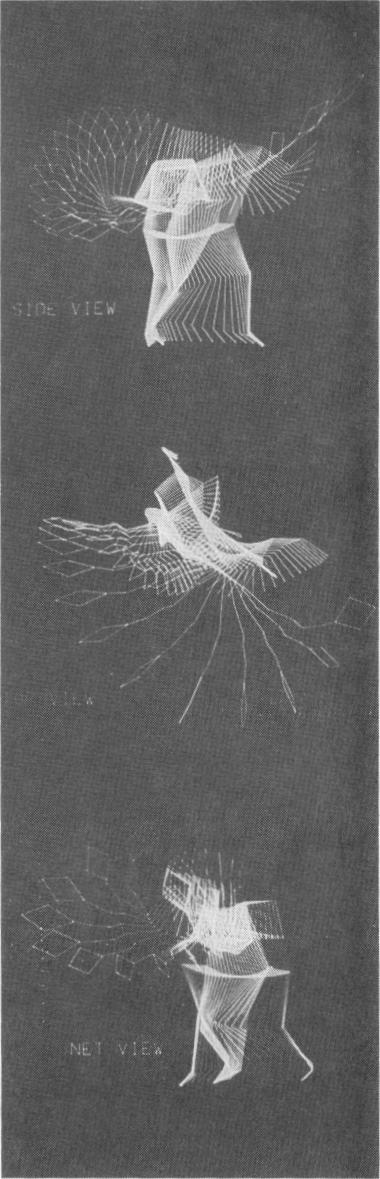

Filming is the first of a series of carefully coordinated steps in the analytical process at Coto. After the film is developed, it is scanned and fed into a computerdigitizer. This process produces little stick figures, enabling Ariel to study an athlete's motions in sequence on the computer screen in three dimensions. He can compare this motion with that of a "model" motion stored in the computer's memory-a tennis stroke, sayand then suggest corrections. Biomechanical analysis by the computer reveals how the motion can be changed in order to achieve the greatest effect. "For example," explains Ariel, "in trying to optimize the performance of an athlete like Jack Nicklaus, once we had his basic swing digitized, we could begin experimenting right on the screen. We might say, 'Jack, we really think you could hit the ball farther by putting your knees in a different position.' We would change the stick figures and the computer could then calculate if we were right. Knowing this, Nicklaus could go to work on adopting a different knee position. He doesn't even have to hit the ball, and we can tell him if this change can help." To prove this principle, Braden and Ariel have begun similar analysis and training of Tim Gullikson, who is rated number 46 in the rankings of the world's top tennis players. If Tim takes to the training, Braden believes, he could soon be giving the likes of Borg, McEnroe, and Connors a run for their money.

One area of research by Ariel and Braden that is certain to be controversial is their work in talent-recognition testing, the early identification of sports superstars. The Soviets and East Germans, in particular, are already using such testing, but many Americans rebel against the idea of "test tube" athletes. In answer to the question, "Do you really want to make robots out of athletes?" Braden replies, "I feel that we owe every youngster proper exposure to the best information we have available. If we're going to make measurements (and every coach does), let's make the best and then give the data to the youngster, the parents, and the coach involved. My goal has always been to create independent thinkers, not robots." F

Computer's-eye view of a tennis player practicing his stroke

DISCOVER February 1981

| Previous | Index |