| Previous | Index | Next |

rotational friction, would have brought the same results.

"I also analyzed Bill Schmidt, the javelin thrower. The computer information indicated he lost force because he dropped his hip. After I pointed that out, Schmidt reached more than three hundred feet, much better than he had ever done."

Last year Ariel studied Kansas City Royals pitcher Steve Busby. "He's getting maximum velocity on the ball with his form," Ariel remarked to the Royals coaches. "But he's going to have trouble with his knee; there's too much stress on it." The K.C. coaches turned pale. They thought Busby's knee problems were a well-kept secret in Kansas City.

With his computations Ariel proves in the following pages that 1936 triple gold-medal winner Jesse Owens actually ran as fast as any current sprinter. Owens, however, was penalized by a slow track. Ariel shows that Soviet high jumper Valery Brumel could leap over eight feet if he'd just pay attention to Ariel's physical principles. According to Ariel's charts, one hundred feet is within reach of modern shot-putters. Finally, Ariel buries that hoary athletic maxim that perfection requires follow-through; he says it is actually counterproductive.

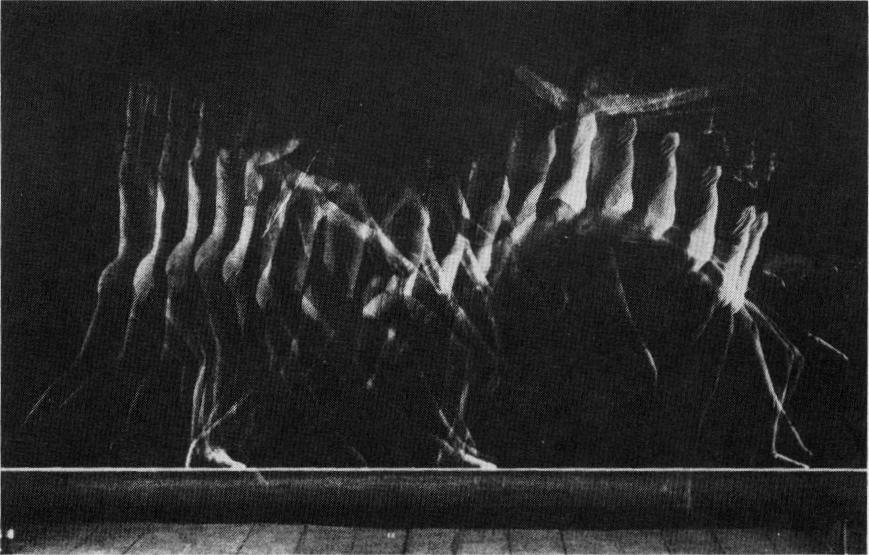

In one Olympic category, gymnastics, perfection is achievable, mainly because scores are rendered by judges, who may

award, if they're so inclined, the highest possible marks to a performer. But when you watch these events on TV, you really can't tell why one exercise is worth a perfect ten while another one, equally amazing to the viewer, registers a less than perfect 9.75.

Muriel Grossfeld, herself a three-time member of the U.S. Olympic women's teams and now the coach for all entries at

Montreal, notes some of the subtleties that escape the camera. "The body must look elastic; at times you must have the quality of dance. The suppleness cannot be just in the legs but in your entire appearance. Difficulty isn't all that counts. A gymnast must be able to move forward, backward and sideward."

She points out that perfection is not a relative quality; a routine movement executed properly scores a ten the same as a much trickier stunt done exactly right. Actually, in women's gymnastics, unlike the male competition, a flub during a

movement of great difficulty is supposed to cost more than a similar error on an easier stunt. The principle is that a woman should not stretch beyond her competence.

Currently training a crop of gymnasts in a converted supermarket in New Haven, G-ossfeld observes that there is a definite advantage for the ninety-pound Korbuts and Comanecis of the world. "Their tumbling radius is so much less than that of tall girls that they can do more in the limited space of a floor exercise. On the balance beam they also have more room to work since they cover less distance with each movement. On the uneven bars if you're tall you come closer to the floor and the bars can be adjusted to accommodate better someone under five feet." Even in training the flyweight females have an edge. They can begin vaults and balance-beam practice sooner than their heavier counterparts because "catchers" can protect them more easily when they miss.

"Tall or long-legged girls seem more graceful," says Grossfeld. On the other hand, the premium on the lower half of the body works against women with big shoulders-and a bosom is just excess baggage.

So let the Games begin, and for the perfection discovered by Gideon Ariel and explained by Muriel Grossfeld, the ones you won't see on the TV screen, read on.

ESQUIRE July 1976

| Previous | Index | Next |