| Previous | Index | Next |

![]()

smashing the old record by nearly two feet. Jokl calls it the greatest single feat in the recorded history of athletic competition.

Was it? Did Bob Beamon reach the limits of human athletic performance on that October day in 1968? In the past, questions like these were likely to be settled by an argument and a wager. But a new field of research into the nature of athletic performance is providing a more scientific basis for the answers. Sports and exercise scientists are measuring and testing everything from athletes' muscle twitches to their mental traits, redesigning their diets and analyzing their physical movements by computer. Although sports science cannot yet predict whether a record like Beamon's will ever be broken, the information accumulated by analyzing outstanding athletes is benefiting aspiring athletes and improving their performances at all levels of competition.

In a sense, the development of sports science is an extension of the older discipline of sports medicine, which can trace its origins to the ancient Greek Olympics. Greek physicians called "gymnasts" were involved in all aspects of an athlete's training. One of the most renowned was Herodicus who was, purportedly, the teacher of Hippocrates, the father of medicine. The American College of Sports Medicine, founded in 1955, continues this tradition with a wide range of

physicians and other specialists as members (including dentists, podiatrists, osteopaths, even veterinarians).

But sports scientists are now interested in far more than the prevention and treatment of injuries. At laboratories from coast to coast, they are studying athletes' physiology, biomechanics, biochemistry, psychology, kinesiology (the science of movement)-from toe to teeth.

An underlying assumption of sports science is that by analyzing the elements of athletic prowess, it should be possible to teach athletes to perform better. But how much room for improvement is there?

For other athletes, improvement may come from understanding physical problems they could not see themselves. Dr. Gideon Ariel, who has specialized in both computer science and exercise science, is training the athlete's neurological patterns and functions as well as the traditional muscular functions by applying computer technology to sports.

The 41-year-old Ariel, a former discus thrower and member of the Israeli Olympic team, has a sports research center near Trabuca Canyon, California, and also conducts studies at CBA (Computerized Biomechanical Analysis, Inc.) in Amherst, Massachusetts. A current prize pupil is Al Oerter, the 43-year-old,

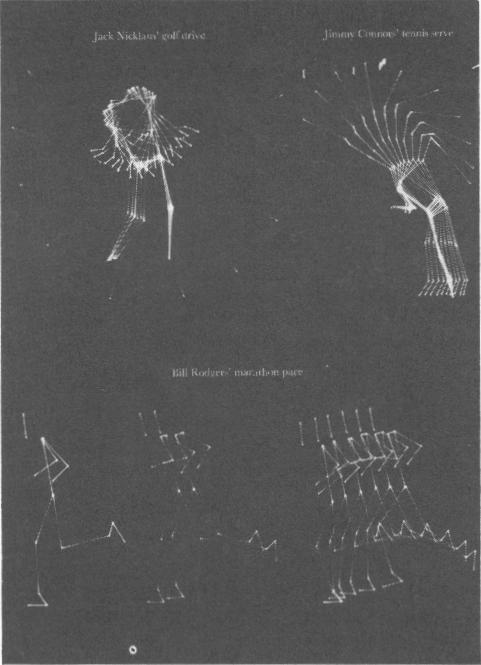

Ariel's computer analyzes athletic performance into

elements, displays stop-action motion on screen.

Images opposite, made from films, show nature of

championship golf drive, tennis swing, marathon pace.

four-time Olympic gold medal winner in the discus, who retired after the 1968 Games and is now making an amazing comeback. Oerter's longest Olympic throw was 212.6 feet (the current record is 233.5).

When he came to me 14 months ago," says Ariel, "we took some high-speed film of him throwing and compared his performance with those of previous years. He is slower, of course; age has slowed him down. But what we noticed was how inefficiently he had been throwing. He released the discus at the wrong angle, causing the throwing forces to be misdirected. The angle of his arm relative to his trunk was wrong for maximum leverage and his feet were leaving the ground when he needed maximum contact with the throwing circle. He was throwing only 180 feet when he came to us."

Ariel made a computer model of the Oerter film, which appears on a graphics display screen like a complex stick man. From this, Oerter could see on the screen right in front of him the elements of his throw. "Coaches can't see the subtleties of where technique is wrong," claims Ariel. "Your eyes can't 'see' forces or velocities. You have to calculate the results of numerous equations and present these graphically on the computer display to see the movements, to see what the athlete must change to optimize his actions and get the most from his force."

SMITHSONIAN July 1980

![]()

| Previous | Index | Next |