| Previous | Index | Next |

![]()

ure, half academy lecturer, half medicineshow barker, a character entirely appropriate to spark the gap, to complete the circuit between science and sport.

Gideon Ariel is a fleshy man, with direct, hazel eyes and a shock of black curls graying at the temples as he enters his 39th year. His accent bears a resemblance to that of Alan Arkin playing Freud in The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, but he shouts more. Occasionally brilliant explications to visitors or students

are followed by awkward silences because his Hebraic rhythms have made "quats" and "kets" of quartz and cats. Because photography is crucial to biomechanical analysis. Ariel speaks often of "ftllums." But it is Ariel's work, not his speech, that has made him a hero to hundreds of athletes.

In November 1975 the U.S. Olympic Committee assembled the 12 best American discus throwers in Los Angeles where high-speed cameras photographed them in action. The film was flown to Ariel's lab in Amherst, where he calculated the forces and accelerations of the athletes' body segments. Ariel himself flew back to California with the results, plopping 50-to-80-page computer print-outs into the bemused throwers' laps. One recipient was Mac Wilkins. The sheets of

numbers meant little to him, but not Ariel's interpretation. "He pointed out that my front leg was absorbing energy that could go into the throw," says Wilkins. "I had to begin to change my whole conception of throwing. I used to think I had to put as much of my speed as I could in the direction of the throw."

Ariel, citing Newton's law about every action requiring an equal and opposite reaction, said no. "It's vital to have everything stopping in the discus. In the

best throws, we found a pattern. It is like using a fly rod, or snapping a towel. You have to decelerate the heavy parts, the legs and the trunk, so you can accelerate the light parts, the arm and the discus." Ariel spoke to Wilkins with special care. because the analysis had shown him generating incredible speed in one section of his spin. "He was like 30% faster than the rest, even though he was dissipating it at the end. But if you see that, you know the potential is there." The computer found that with a perfectly timed summation of his forces, Wilkins could throw the discus 250 feet.

"It seemed a little far at the time," says Wilkins, whose best was 219' I ". Indeed, the world record was 226' 8". But the second and third times Wilkins put Ariel's advice into practice. he broke the world

record, eventually reaching 232' 6" and winning the Olympic gold medal at Montreal. He continues to throw, calmly maintaining he has not lived up to his potential, and for once that is a judgment supportable with clear evidence.

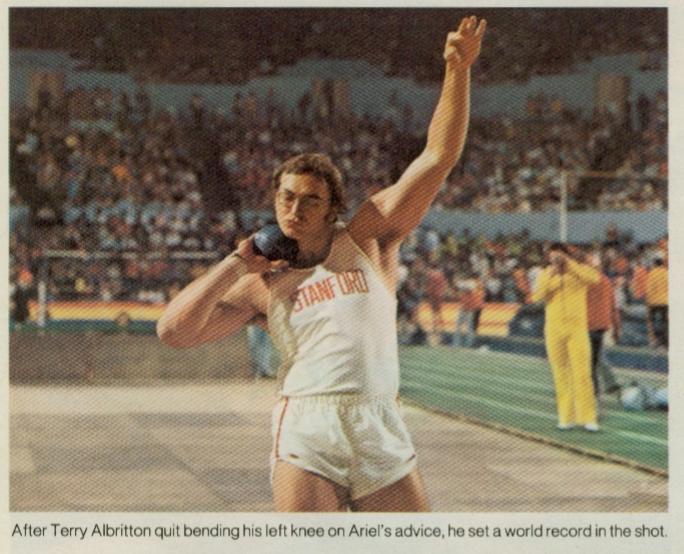

Shotputter Terry Albritton's mistake was similar to Wilkins'. "That front leg has to be the solid block you throw from," says Ariel. "What Terry was doing, bending that knee, was like trying to throw from a trampoline or shoot a cannon from a canoe." A year ago Ariel told Albritton he could be the next world-record holder if he'd stop doing that. A month later Albritton was the next world-record holder, with a put of 71' 8%j".

Sometimes the camera and computer happen upon events that bluntly refute accepted theory. Long jumpers have all trained by rising to their toes under heavy weights, strengthening their calves for the last push from the hoard. Ariel's analysis showed, however, that the best jumpers don't point their toes until the pushing foot is already two feet off the ground. "Far more important than the jumping leg is the free leg," says Ariel. "It and the torso accelerate as the planted leg decelerates. Then the jumping leg is yanked off the ground. That leg isn't pushing„ it's trying to catch up."

In a study of Kansas City Royals pitchers, another commonsense belief fell to clear measurement. "You'd think if the forearm muscles that flick the wrist were stronger, you'd move the wrist faster and throw harder," says Ariel, illustrating by flapping a limb in the manner of a rather aggressive princess thrusting her hand out to be kissed. "But no. Because of the whip action, the concentration of force from the legs and back and shoulder, the forearm is like the end of that snapping towel, the wrist snaps far faster than any muscle can contract. It just goes along for the ride, so it is absolutely useless to train the wrist."

No sport is immune to Ariel's iconoclastic examination. Not long ago, he and his staff spent 4,000 hours analyzing the behavior of tennis balls, filming them at 10.000 frames per second as they struck rackets and assorted surfaces.

"Tennis people think they can feel the ball on the racket. They talk as if they can do things to control it then," says Ariel, waving an imaginary racket. "We

56

![]()

| Previous | Index | Next |