| Previous | Index | Next |

![]()

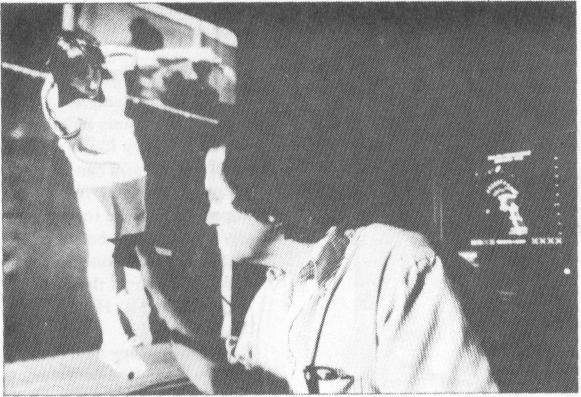

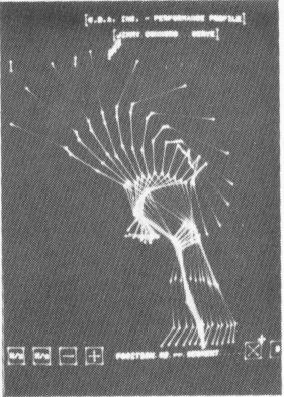

To analyze the body's efficiency, Ariel runs a film of the athlete through a computer, freezing each frame and measuring critical angles and lengths with a magnetic pen (left). The computer then creates a schematic printout (right)-in this case, of Jimmy Connors as he serves.

discus with characteristically singleminded passion and energy.

He got good enough to make the 1960 and 1964 Israeli Olympic teams, but that only bespeaks the lack of athletic talent in his native land at that time. Ariel was no world beater. His best Olympic toss was 171 feet when the gold medal was won with a throw almost 30 feet better. If he had had his present technology, would he have become a champion? "I was always very nervous in competition," Ariel responds, "and science hasn't worked out the emotional part

... yet.,,

Although Ariel has made a smooth transition to the teaching side of sport and become an evangelistic professor of physical movement, he makes no claim of originality in his work. The use of high-speed photography to scrutinize and measure physical motion goes back to the 1870s when it was employed to prove that a running horse lifts all four hooves off the ground at the same time. In the 1930s, with better high-speed cameras, people were measuring and charting the acceleration and deceleration of body segments. Ingvar Fredricson, a Swedish biomechanic, was using a computer to study motion patterns almost ten years before Ariel, and at Penn State University, Peter Cavanagh has been studying human stride patterns for a number of years.

Ariel began his involvement with hiomechanics in 1966 at the University of Massachusetts, where he studied exercise science and received a masters degree in nine months (he had previously

received an undergraduate degree in physical education from Israel's Wingate Institute). Later, he took courses in computer programming and then spent seven years and some 10,000 working hours creating the initial programs that guide his computer.

A staunch advocate of the free-enterprise system, Ariel is getting his message across and earning a living at the same time. In 1971, he founded Computerized Biomechanical Analysis, Inc., in Amherst, Massachusetts, and through it sells his unique services. At first, his clients were almost exclusively manufacturers of athletic equipment, but as his reputation has grown, many professional athletes have sought his expertise. For example, pitchers on the Kansas City Royals baseball team came under Ariel's scrutiny and were told that it was "useless" to build up their wrist strength for throwing a faster ball, because, as Ariel showed them, the wrist simply goes along for the ride. The concentration of force from the legs, back, and shoulder creates the power thrust; the forearm is like the end of a snapped towel, and the wrist snaps far faster than any muscle can contract.

Ariel's findings have shown that "stepping into the ball" is not necessarily a good idea for baseball hitters, because the key to power-as the good shot-putters and discus men now know -is well-stabilized, stationary legs. "If nothing else," Ariel notes, "the trunk of the body should come to a stop at contact with the ball." Old baseball hands will recall that Joe UiMaggio, a

pretty fair hitter, stood at the plate with his feet very wide apart and took almost no step into the ball. It is more than likely that "Joltin' Joe" came to his method either by accident or instinct, and indeed, some of what Ariel has discovered about athletic technique had been guessed at previously by athletes.

In his analysis of the golf swing, for example, Ariel compared slow-motion film of Jack Nicklaus and former President Gerald Ford-one a pro, the other an "average golfer"-and concluded that by rotating the hips rather than sliding them sideways, the golf shot can be hit with more power and greater control. Most serious golfers have recognized this truth, but usually only after considerable and sometimes painful experimentation.

With the help of his CBA staff, led by his computer-specialist partner Ann Penny, Ariel has analyzed how tennis balls behave when struck with a racket. Among his findings was the fact that the ball is on the strings for only four milliseconds. Since human reaction time, according to Gideon, is on average 100 milliseconds, the ball is long gone before one feels the impact from hitting it. Thus, tennis players don't have nearly the control over a ball they've hit that they'd like to think. "In fact," says Ariel, "they have none." All the more reason to anticipate play and get the racket hack early.

Because sports performance depends so much on a firm, stable footing, it should come as no surprise that Ariel has a special interest in athletic shoes.

USAIR MAGAZINE October 1980

![]()

| Previous | Index | Next |