| Previous | Index | Next |

![]()

plying that knowledge to the pursuit of athletic excellence.

At first it was work done on a shoestring-and a time-sharing computer. Without a university connection or outside funding, his company, Computerized Biomechanical Analysis (Amherst, Mass.), sought contracts from equipment manufacturers, and he worked with athletes only as time and money allowed.

Braden learned of Ariel's work at the time he was negotiating with a real-estate conglomerate to establish a tennis college at the lush Coto de Caza resort community 70 miles south of Los Angeles.

"I had been doing high-speed cinematography for years," Braden told me. "What I didn't have-and wanted desperately-was a way to quantify the forces. Gideon gave me that." The tennis school was established only after the owners agreed to finance a complete sports-research center.

Since that time, a steady parade of champions-from Muhammed Ali to Spectacular Bid-has been digitized at the center. The basic procedure begins with the filming of an athlete's motion with several cameras from two or more angles. Then the films are projected-frame by frame-on a special Graf-Pen digitizing screen, on which relevant parts of the athlete's body are traced with a magnetic pen (photo, facing page). The information is then processed by Data General computers, which feed it back out as three-dimensional stick figures on a Magatek graphics terminal.

The digitizing method is. not unique to Ariel. His special contributions have been in the area of softwareprograming that smooths the digital signals and manipulates the data. "We built constraints into the program that tell the computer, if the ankle is here then the knee can't be over there," he told me. "Otherwise, we'd have heads detached from bodies and legs all over the screen."

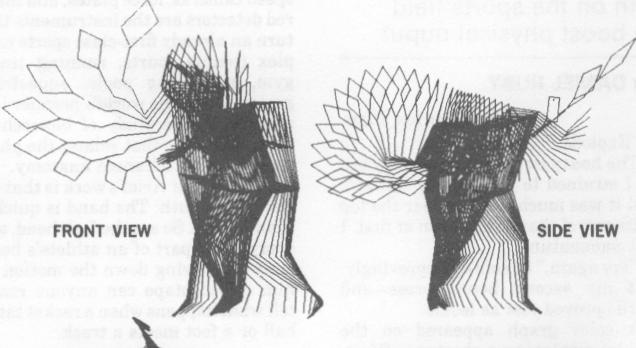

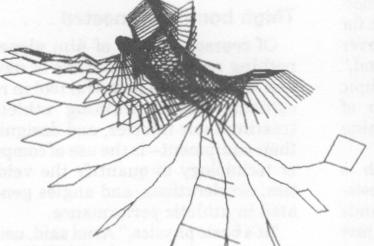

With just the position data fed from the digitizing screen, the computer is able to display the action in any orientation-front, side, or top view. It can plot velocity and acceleration along each axis. It can create graphs showing changes in center of gravity or other indicators. It can call up stored data to compare athletes. Or, supplied with new variables, it can calculate the effects of changes in technique.

Digitizing from film is expensive and time-consuming, however. "The future is in real-time digitizing," Ariel said. He is working with both video and infrared-sensing technologies to develop a system that can provide

Continued

Digital stop-action tells the story

TENNIS

TOP VIEW

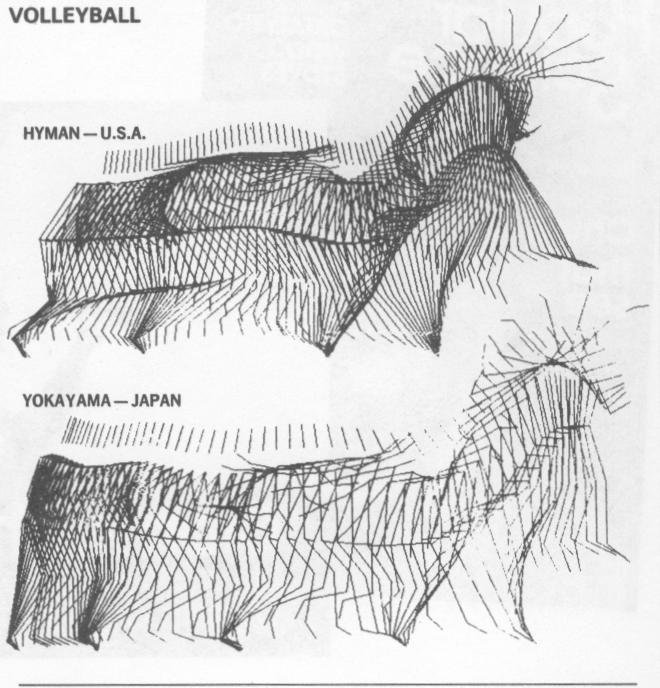

Computer comparison of two volleyball spikes (top) shows that though the American player jumps higher, she hits the ball on its descent and is not fully extended at impact. Japanese player got greater velocity. Three-axis representations of motion-tennis pro Tim Gullickson's backhand (bottom)-are generated by correlating data digitized from any two camera angles.

POPULAR SCIENCE January 1982

![]()

| Previous | Index | Next |