| Previous | Index |

![]()

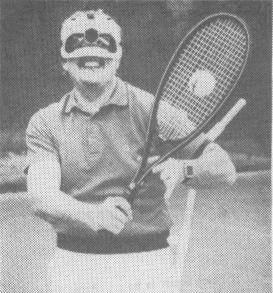

Keep your eye on the ball, coaches say. But now they can follow exactly where eyes are focused with the fiber-optic camera in the recorder helmet Vic Braden is wearing (top left). Pipes strapped to his body help demonstrate the whipping

instant analysis. So far, video lacks the necessary resolution.

He has had more success with a device called Selspot, which uses infrared light-emitting diodes to give position information. Ariel showed me a golf club he has rigged up to use the system. A tangle of wires led to an array of LED's lining the shaft and head of the club. Each diode puts out thousands of signals a second, which are picked up by two cameras and fed to a processing unit. Any golfer swing

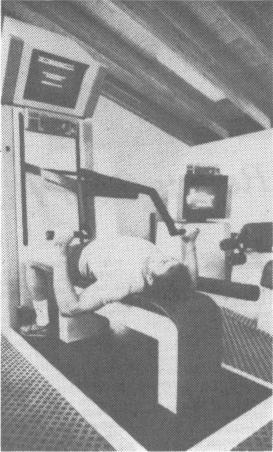

action of body segments. Gideon Ariel's computerized weight machine (top right) uses hydraulic valves to provide variable resistances that match precise training needs of any sport. Above: Ariel views video display of Jimmy Connors' serve.

ing the club gets an immediate threedimensional analysis of his swing.

"It's probably the world's most advanced system," Ariel said. "But there are problems. Reflections can create spurious data. It requires an external power supply. And those diodes can get hot, so if we use them on an athlete's body, they affect performance."

Nevertheless, Ariel is impressed enough with the potential of the device that he developed the necessary programing for calibrating and

processing the digital signals. Selective Electronic, the Swedish company that markets Selspot, will use his software in selling the system to medical and industrial users.

... to the hip bone

While the fully electronic systems get further development, Ariel continues his work with film. The center's most recent success came last year with the American women's volleyball team, which had been losing consistently to the Japanese, Cubans, and others. The first step in improving the team was "spying" on the opponentsthat is, filming them in competition. "There's no way they could hide their technique," Ariel said. "If they did, they'd lose anyway."

By digitizing and analyzing the action, he was able to ascertain how best to time a spike, how to move laterally on the court, and other vital factors. Then the team's coach used this information to teach the players, who actually trained at Coto. Result: an unbeaten record on a recent world tour. "Now other countries are filming us," Ariel said.

Besides optimizing performance, Ariel's computers are used for:

• Equipment design. "For years, sporting-goods manufacturers were in the dark ages," Braden told me. Now many are coming to Ariel for data. And he himself has designed running shoes, tennis balls, and other gear. Wilson Sporting Goods will market his revolutionary weight machine.

• Talent recognition. Youngsters are tested for coordination, reflexes, and muscle development to determine which sport they will excel in. Early recognition of talent can lead to championship form, as Braden's coaching of a two-year-old named Tracy Austin later proved.

• Non-sports applications. Ariel recently performed a study for a diaper manufacturer that showed that its product can cause knee injuries in babies. He has also worked on designs for better ketchup bottles and matches. And insurance companies often seek his services to verify claims. "We can tell in a few minutes if someone with a back injury is faking or not," he said.

Such work is certainly lucrative for the center, but the former athlete's key interest remains athletic performance. I asked him if there is such a thing as a perfect athlete. "Oh sure," he said. "In the explosive events particularly there are limits. After that, something snaps. For anyone to do much better than the current records in the sprints, they'd need tendons made of steel, not protein." m

MELODY BRADEN

POPULAR SCIENCE January 1982

![]()

| Previous | Index |